Features

Associations

Business

Examining contaminants

What contaminates ground water drinking supplies?

April 6, 2011 By Ken Hugo

After a groundwater supply system is developed and up and running, the ground water is generally pretty safe from contaminants. The ground water has likely been in place for hundreds of years, and if the water is good to start, chances are, it will remain that way.

After a groundwater supply system is developed and up and running, the ground water is generally pretty safe from contaminants. The ground water has likely been in place for hundreds of years, and if the water is good to start, chances are, it will remain that way.

But things may change, even in an established ground water system. Contaminants may enter the ground, or may be introduced in the well or the plumbing system. Even standards may change – somebody may have a system that provides acceptable water one day, but if the standards change the next day, the water may be considered out of compliance with drinking water standards.

In the United States, community water supplies have to be tested and the results must be sent to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The EPA has prepared a report summarizing violations within their community water supplies, and it is informative to examine this report and see what is contaminating the ground water.

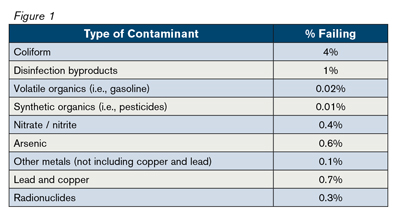

Of the 155,000 systems that were monitored, 92 per cent of them are always in compliance. The figure rises to 97 per cent when temporary exceedances (i.e., a short-term failure after a storm event) are excluded. The EPA report summarizes the systems that fail as in Figure 1.

|

|

Coliforms and other pathogens are the most common contaminant in ground water and of such concern that a recent issue of the National Ground Water Association’s technical journal (Ground Water) spotlighted research on these contaminants. According to this journal, about half of disease outbreaks related to water supply are caused by contaminated ground water: not necessarily from the aquifer, but perhaps introduced in the pumping and distribution system.

Pathogens are not usually found in ground water for several reasons. Bacteria that thrive in humans or animals do not find a very hospitable environment in the ground – it is too cold, not acidic enough and their food sources are not as plentiful. Natural bacteria will consume pathogens. The pathogens can be caught up in material around pores in the rock.

Although ground water is largely free of pathogens, let’s discuss situations that might put ground water at risk:

- Proximity to source – wells close to feedlots, manure storage areas and septic fields are more susceptible to contamination. Many provincial water well regulations require setbacks from septic tanks, septic fields and direct sewage discharge points. Manure storage and collection facilities are also required to be set back from a water well.

- Direction of ground water flow – wells down gradient from the contamination sources are more susceptible to contamination moving along with the natural ground water gradients. As a result, wells should be placed up gradient (usually higher) than sources of contamination. Whether this can be done in a community with many wells and septic fields is open to question. Ground water may not always flow in the direction of the local slope, and ground water pumping may reverse ground water flow directions, so just placing a well uphill from the closest septic field is no guarantee that the well is up gradient from all sources of contamination.

- Depth to the water table – pathogens do not do well in moist, unsaturated soils where they have to compete with other forms of bacteria, which thrive in these environments. This is why septic fields have unsaturated soil below the infiltration point of septic effluent.

- Type of aquifer – Typically, ground water has to flow around a tortuous path past grains of rock. Pathogens can be caught or trapped by organic material that may be found lining the grains within the aquifers. Aquifers that have a relatively small amount of pore lining material can be very productive. Examples of these are fractured rock and karst aquifers. The Ground Water issue illustrates that many instances of pathogen contamination are found in these aquifers where water can flow at very high velocities, without making too much contact with rocks. This trapping of pathogens is why septic fields should be placed on finer grained soils (generally silts are about the best), and not directly above bedrock.

- Well design – While not covered in the Ground Water issue, well design can lead to contamination by pathogens. Direct flow of surface water into the well can introduce pathogens. Well pits are no longer allowed to be constructed because these pits allow too many pathogens to enter the water. Cisterns, which are not part of the well, but part of the ground water supply system, can also be a source of contamination if not properly connected or sealed.

Water well drillers generally do not have much say about septic field design or placement, but when drilling a well, they should bear these factors in mind. Make sure appropriate setback requirements are followed and that wells are not directly downhill from any sources of pathogens. If shallow bedrock is found, make sure that adequate surface casing is installed and sealed. Old, unused wells can be contaminant migration pathways to the aquifer, and abandonment of unused wells or wells in pits should be strongly encouraged. Testing of the water for water quality purposes should be carried out as a matter of routine, especially when some concerns are raised as to the quality of water.

|

|

| An Alken Basin Drilling Ltd. rig on the plains of west central Alberta. Drillers may not get much input into septic field design or placement, but it’s still important to keep those factors in mind when drilling. Photo by Ken Hugo

|

Pathogens tend to rest on the pore surfaces and can be disturbed when first pumped. One of the articles in the Ground Water issue shows how coliform bacteria can be present when pumping starts, but quickly decline to below detectable limits after one or two well bore volumes are pumped. Typically, in a pump test, water samples are collected towards the end of the pump test to obtain a true ground water sample, but most people do not run the pump for two hours before filling a glass of water, so collecting water samples when the pump is first turned on might be a better practice.

Of the other types of contaminants, no category represents more than one per cent of systems. Contamination by disinfection byproducts is the next highest form of failure and indicates that adjustment to the treatment system is required.

Various forms of metals are the next highest category of failure. Plumbing features themselves may introduce contaminants such as copper and lead. Recently in the United States, the allowable amounts of lead and arsenic in the ground water have been lowered and it is probable that some failures are a result of systems that were acceptable when first installed, but became failures when the standards changed.

Other metal contaminants, such as arsenic, may be present in the aquifer naturally, but sometimes a change in the ground water conditions due to human activities (such as acid rain) may mobilize these metals into the ground water, causing a problem. A strong case can be made that testing for metals should be done as part of a routine water analyses package.

It is interesting to observe that much concern has been raised about contamination of ground water drinking supplies by organics, whether from petroleum fuel products or insecticides and herbicides. The data show that only a very small proportion of the water supplies (about three in 10,000) have been contaminated by these products.

Radionuclides contaminate ground water at a relatively high rate. There is growing awareness of their potential to contaminate ground water is slowly being realized. Many provinces do not require testing for radionuclides, so it is hard to determine whether they are an issue.

So can a ground water system that initially provided clean water become contaminated? As the incident at Walkerton, Ont., showed, the answer is yes – although Walkerton was a case of surface water entering the water distribution system. Other contaminants may show up with time – bacteria starting to grow in the well and elevated metals are the two most likely. The chances of this occurring, while slight, are high enough that continual monitoring is required to ensure that the public is protected and continues to enjoy safe water supplies.

Print this page