Features

Drilling

Guard or Kill Switch?

Changes in Quebec prompt safety discussion

September 2, 2014 By Carolyn Camilleri

June 30 was an important day for well drillers in Quebec: that was the deadline for installing a new emergency-stop system on drills to comply with CSST requirements.

June 30 was an important day for well drillers in Quebec: that was the deadline for installing a new emergency-stop system on drills to comply with CSST requirements.

|

|

| Simon Massé of Puitbec Groupe developed a device to satisfy the requirements of the CSST and allow drillers to work without the auger guard. Photo courtesy of Simon Massé, Puitbec Groupe Advertisement

|

It wasn’t a change to the regulations, something quickly pointed out by Gilles Doyon, executive director of the Association des Entrepreneurs en Forage de Quebec, which represents drillers. “There is absolutely no new regulation about the new emergency-stop system,” says Doyon.

However, not installing the new system could result in a fine under the general regulations of the CSST for having not taken all due measures to protect workers from danger in a sufficient and adequate manner, says Doyon.

So how can non-compliance with a non-existent regulation result in a very real fine? The new device is a CSST-accepted “exception” to a regulation that no one has followed for years, but has lately been the cause of much discussion and expense.

And no one has discussed it more than Simon Massé of Puitbec Groupe in Victoriaville, Que. A strict reading of the regulations, says Massé, means that any rotating auger must be surrounded by a guard or fencing to prevent someone from falling against or being caught in it.

“Other augers, like those used for diamond drilling, drill very fast and are quite different from ours,” says Massé, adding that in the case of other drills, the regulation makes sense. “They have to use a guard, but not us.”

Massé says the guard does not improve safety with water well rigs and makes it impossible to work efficiently.

“No one uses a guard,” says Massé, explaining that, in the past, CSST inspectors understood that water-well drills were different from, say, diamond drills, and life and work carried on in Quebec. Until recently, that is, when a CSST inspector stopped and sealed one of Massé’s rigs.

Darren Juneau, president of the Ontario Ground Water Association (OGWA) and CEO at Aardvark Drilling, calls auger shields a “hot topic” in Ontario as a result of a fatality in Hamilton in October 2008. The tragedy was blamed on the lack of an auger shield, as well as the lack of a wobble switch or spindle brake on the older-model drill.

What could have saved the worker: a drill shield or a stopping device?

In Ontario, there is no specific reference to an auger shield. Construction Regulation O. Reg. 213/91, s. 109 reads: “Every gear, pulley, belt, chain, shaft, flywheel, saw and other mechanically operated part of a machine to which a worker has access shall be guarded or fenced so that it will not endanger a worker.”

“My interpretation of the legislation is that to be in compliance, a physical barrier is required to prevent the inadvertent contact of the worker with the drill string,” says Juneau. “A kill system is not sufficient because a worker has to become entangled in the drill string to hit the switch. The legislation is written to prevent a worker from ever getting to that point.”

In B.C., drill guarding is not a legal requirement but it may be a request from clients.

“There is no law requiring drill guarding in B.C.,” says Collin Slade of Drillwell Enterprises in Duncan, B.C. “We have guarding that we use with our augers when requested.”

In Ontario, the drive for string fences or guards was spurred on by engineers and planners rather than the Ministry of Labour (MOL), says Juneau.

“But there was no consensus, so the larger firms demanded they be present or we couldn’t work for them, and the smaller firms bemoaned the 33 per cent loss of productivity,” he says. “To go one step further, the larger firms differ from office to office, so some offices would be sticklers and send us home if they didn’t like the drill string fence we came up with, and other offices would not like them on site at all!”

That 33 per cent loss in productivity is a sticking point – using the guard adds extra steps.

“There are several operations during the course of drilling which require the guard door to be opened, for example when adding or removing augers, taking samples, etc.,” says Slade. “There is definitely a perception out there that they don’t add a lot of value where the people operating the equipment are properly trained.”

While drill fences reduce productivity by one third, says Juneau, “kill switches alone have a nominal effect on productivity.”

Juneau points out the significant problem of equipment that isn’t manufactured with the safety features because it means installing aftermarket systems.

“At minimum, toggle kill switches should be present to stop the rotation of the drill string should someone become entangled. Guards or fences are also encouraged but as of yet there are no requirements – other than to adhere to the legislation – for the design and upkeep for aftermarket safety add-ons, which can be a safety issue unto itself.”

Juneau says the situations in Quebec and Ontario are similar.

“The equipment manufacturers do not offer physical guarding or fencing for their machines because it is not practical and limits the use of the equipment,” he says. “The MOL– or CSST in Quebec – insists that safety systems are installed but the manufacturers do not produce such a product. So our members are forced to generate their own version of a guard or fence or kill system.”

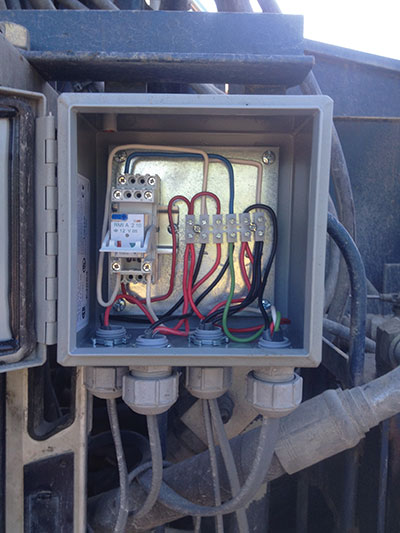

That is what happened in 2008 — the company owner had an auger shield specially designed. Massé did the same by developing a device to satisfy the requirements of the CSST and allow drillers to work without the auger guard. Basically, it is a bar connected to a switch that automatically stops the drill if anything falls against it. For CSST compliance, the device must be designed, installed, and certified by an engineer and a maintenance procedure must be followed.

“The new system is not a regulation but rather something the CSST will tolerate instead of the old-style auger guard,” says Massé. “What the law requires is a guard for the drill, but it is impossible to work with a guard. We have created the device not because there is a danger but rather to keep [the CSST officers] away from us.”

Slade also questions the value of the guard, saying there is some hesitation because guards potentially introduce the hazard of another pinch point and are another piece of equipment to work around.

“To be clear: although the guard is difficult to work with and doesn’t provide much, if any, additional safety and in certain operations it does need to be removed, it is possible to work with guarding and prevent people from falling into equipment. It is just of questionable value,” says Slade.

The cost – whether for auger fences or kill systems – is another concern. Massé says the new stopping system costs between $3,000 and $8,000 per rig, depending on the hydraulic components. The individual companies are paying for it. Of course, the companies can use the auger fencing instead, but because it isn’t standard, that also carries a significant cost.

“On average, our drill fences cost $7,000,” says Juneau, clarifying that he is referring to Aardvark Drilling and not OGWA in general because no data has been collected from members regarding this matter. “[Aardvark] operates 13 drills so I have spent in the neighbourhood of $100k in the last five years addressing this issue.”

Ralph Jacobs of Blue Nose Water Well Drilling in Lawrencetown, Halifax County, has been watching the activity in Quebec with interest and feels the new system is something all provinces should be considering, particularly if it improves safety.

|

|

| Basically, Massé’s device is a bar connected to a stopping switch (pictured) that automatically stops the drill if anything falls against it. Photo courtesy of Simon Massé, Puitbec Groupe |

“So I am saying yes, if it is a safety issue and if the department of labour is involved, then there should be some incentive that every drill rig get this done,” says Jacobs. “But we should be compensated somehow through a grant or whatever the government can come up with to help us out.”

But what does improve safety?

“Emergency stops are standard safety measures on B.C. drills,” says Slade. “All of our equipment has emergency stops because there is certainly value in them. The ability to stop a piece of equipment is a requirement.”

Most important, says Slade, are proper training and safe work procedures.

Ellaline Davies, president of Safety Works Consulting, says that, in the past, the issue has been around the ability to perform the task and operate the equipment properly.

“Because it is so very difficult to work with the guards, most businesses have relied very heavily on making sure that the operator is very, very well trained,” she says.

A problem Davies identifies with the Quebec situation is that the rules were made carte blanche for all drills. “It would be really, really hard for people doing another kind of drilling if the purpose of the regulation was to take care of one particular sector.”

For Juneau, however, a carte blanche rule would provide direction and level the playing field. “What is acceptable by one company is not acceptable to another company and the same is true for MOL inspectors. You are in compliance one day in part X of the province and non-compliant day two in part Y.”

Because of the challenges in interpretation, there have been calls to create a standardized safety manual — something not easily developed.

“Every single sector wants a one-size-fits-all manual, but everybody does things differently,” says Davies. “Smaller companies of five or less employees are still held to the same standards as the companies with 200 or 500 employees. Obviously it looks very, very different.”

The MOL requires companies have their own manuals. Templates are available that “cover off the umpteen varieties of things that your company might have to have incorporated,” says Anne Gammage, office manager at OGWA.

“The whole purpose behind it is to develop management systems for health and safety,” says Davies. “It is about making sure that, if something goes wrong, people are not held accountable for things that they didn’t even know were even in their manual.”

Returning to the situation in Quebec, Davies says, “A key part to this and any job is hazard recognition, risk assessment and then putting controls in place.”

Controls that then become regulations.

“Regulations must be practical, effective and accepted by workers and industries to be effective,” says Slade. “Consultation is critical to ensure the effectiveness and implementation of regulations.”

Carolyn Camilleri has been a writer and editor in Victoria for the past 15 years and now divides her time between Toronto and Vancouver Island, writing for several trade and consumer magazines across the country.

Print this page