Features

Business

Success Stories

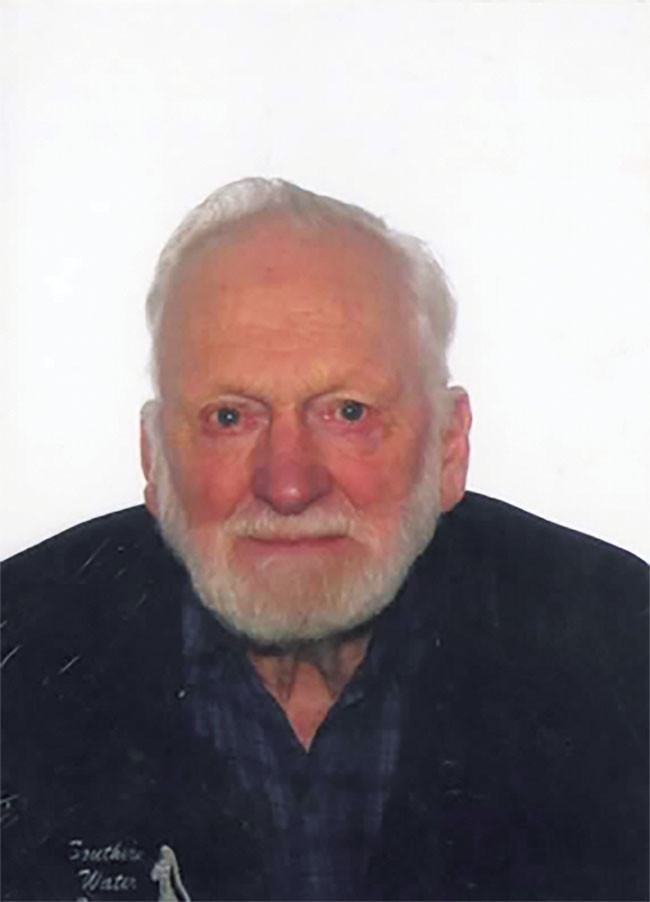

Lewis Hopper: Champion of the drillers

Lewis Hopper advocated for aquifers and drillers

August 21, 2018 By Colleen Cross

Longtime well driller and government liaison to the drilling community Lewis Hopper had a remarkable life and career.

Longtime well driller and government liaison to the drilling community Lewis Hopper had a remarkable life and career. Not many people can say they have drilled in every province in Canada over more than 70 years, yet that was the case with Lewis Hopper.

The longtime well driller and government liaison to the drilling community died in Brandon, Man., on July 4 at the age of 89 after a courageous battle with cancer and a remarkable life and career.

Hopper began his water well drilling career in the 1945 in New Brunswick, and worked in Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Quebec, before joining International Water Supply in Saskatoon from 1959 to 1975.

He worked for the Manitoba government for 23 years – first for the Manitoba Ground Water Section out of Winnipeg from 1975 to 1989, then in the provincial lab in 1989, and finally for the Manitoba Water Services Board in Brandon.

From 1998 to 2017 he consulted independently as Hopper’s Well Service Ltd.

That is an outline of his career, but there is a richer story to tell. Lewis Hopper did a lot for Manitoba, said friend and associate Ryan Rempel, formerly of Friesen Drillers Ltd., who worked with him for some 35 years beginning in the 1970s. “In its infancy the MWRB was a busy and energetic place and Lewis was a big part of it,” wrote Rempel in an email.

“He was hired in part to be a liaison between the department and the drillers. Well, he was that and much more. He was a mentor to many of the drillers, a troubleshooter (and a troublemaker at times to some), a driller, a pump installer. You name it, Lewis did it all.”

In his memorial tribute, his friend Les Connor, former owner of Paddock Drilling in Brandon, Man., described some of Hopper’s most significant contributions to the industry. “One of the common problems at the time, was that because of the limitations of older well drilling methods – there were many wells that were producing sand with the water. . . . . Along with Lewis’ colleague at Water Resources, Arne Pedersen, a standardized method of well construction was developed to drill sand-free wells. It was Lewis’ challenge to convince the well drillers that this new method worked, show them how it worked, and that they could make money with it. It was a success, and over a few years most of the sand-producing wells were repaired or replaced. The technique became standard practice, and is still standard practice, for well construction today. Tens of thousands of Manitoba residents that rely on wells for their water supply continue to benefit from this work to this day.”

Hopper was an innovator who was instrumental in solving many well drilling and maintenance problems, Connor said in his tribute. “He made up a variety of tools and equipment such as fishing tools for retrieving items dropped down or stuck in wells, frost-free packers, flow through packers, sand feeders, jetting tools, frost-free hydrants, cutters and scrapers for cleaning wells, and tested many of the recommended well cleaning chemicals that were available at the time. Many of these inventions, tools, and techniques have become standard operating procedure and are in use today by well drillers in this province and beyond.”

Kim Poppel worked with Hopper in later years. Poppel closed wells for Manitoba’s water authority, sealed abandoned wells and cleaned reservoirs.

“I told Lewis, ‘You’re full of stories. Write this stuff down.’ ” Together they did just that, exchanging pages and getting down details of his life, career highlights and opinions informed by years in the field. Les Connor and Ryan Rempel reviewed the memoirs.

“Initially, there was a lot more steam,” Poppel said with a laugh. “But we left in just enough crotchety.”

Hopper was pleased to have finished the writing project. “Kim encouraged me to put something down on paper,” Hopper said in an interview with Ground Water Canada in June. “She did a great job getting it down.”

Although Hopper first harboured doubts about working for the government through the Manitoba Water Services Board, it was a career move that brought him a lot of satisfaction.

“I was not impressed with going with the government back in 1975, but I promised my brother on his deathbed that I would apply for it and I got the job,” he said during our interview. “But, you know, it was one of the best things that ever could have happened. These Manitoba well drillers were just the greatest guys to work with you could get.”

He was not shy to question government authorities on matters of drilling and water quality, and encouraged other drillers to do the same. “Don’t ever think you are below anyone; engineers got their education studying what the working class learned and gave away. Someone was then smart enough to get it down on paper so it could be studied to become an engineer!”

Despite his awareness of two camps, Hopper said he learned a lot from engineers.

“We have some good engineers. They had to be good to put up with me,” he said with a laugh. “If I didn’t like something I said so. I didn’t back up when I thought I should go ahead.”

One engineer Hopper admired for his humility was Arnold Pederson. “Arnold was down as low as anyone could go to work with drillers,” he said.

His rapport with drillers sometimes gave the board cause for concern. “I had one of my bosses tell me I couldn’t be doing a very good job because the drillers thought I was OK. I said, ‘If you can’t work with them and have them on your side, you can’t do a proper job.’ ”

Hopper rose to the challenge of taming high-pressure flowing wells, one of which, he recalled, flowed at 1200 gallons per minute, 82 feet above ground. “I think the high-pressure flowing wells we got under control were the biggest challenge, and the most fun. They were something you really had to buckle down on to figure out and as long as the government would let me hire the people I wanted, we could seal them.”

What’s changed over years? “Knowledge on how to handle some of these terrible, fine, silty formations. . . . We have drillers that can put wells in places you wouldn’t even try to put a well in,” he said.

He agreed that finding and retaining good workers across this industry is a challenge and had a theory about why. “For one thing, it’s hard work: heavy, dirty, hard work. It doesn’t pay real well. And you’ve got to be on the ball or you’re not much use to the other guy. One of the big things is being able to look at problems and not get excited,” he said. “I tell people, ‘Just remember, somebody else made this, and you should be able to fix it.’ ”

Hopper clearly had drillers – and everyone – on his side, and the evidence came in the form of a restored 1942 Studebaker pickup a group of his government colleagues, well drillers and suppliers presented him at his retirement picnic.

“Needless to say, both my wife, Joyce, and I were in shock and disbelief,” the newly retired driller wrote in his memoirs, “and as some of the drillers said, ‘Hopper was speechless.’ ”

The Hoppers, who have four children – Rick, Bernard, Scott and Maureen – since the mid-1990s, have made their home in a small community in a glacial moraine, at the base of a hollow overlooking Manitoba’s Lake Clementi.

These words from Ryan Rempel seem to sum up the feelings of Hopper’s friends and colleagues: “The preservation of the aquifers and ground water and the preservation of the drilling trade and its drillers were two of his passions. He did a lot for both. There is a big hole in the ground water industry. RIP, Lewis.”

Read Lewis Hopper’s memoirs, Lewis Hopper: Canadian Well Driller.

Print this page